Story & Photos by Kelly McGreal

If you enjoy spotting feathered friends in Cuyahoga Valley National Park (CVNP), fall is an exciting season. Every year, billions of birds migrating south pass through our region. Some species, like the Yellow-rumped Warbler and the Hermit Thrush are short-distance migrants while others such as the Tennessee Warbler and Swainson’s Thrush make an epic journey to Central and South America.

During their passage, migrants need places to rest since they fly continuously through the night. Habitats within CVNP offer traveling birds a stop or “layover” during migration to feed and recover before continuing their trip. While they’re here, park biologists have a unique opportunity to study these migrating birds. Using a bird monitoring protocol, they briefly capture birds, affix a uniquely numbered band to one leg, and record data.

Even though biologists can monitor birds by observing them at a distance using binoculars, CVNP park biologist Mariamar Gutierrez explains the benefits of bird banding:

“When we have a bird in the hand, it gives us a wealth of information we can’t get otherwise. Bird banding is an incredibly valuable, scientific tool that allows us to really learn about the demography of the birds we have in the park.”

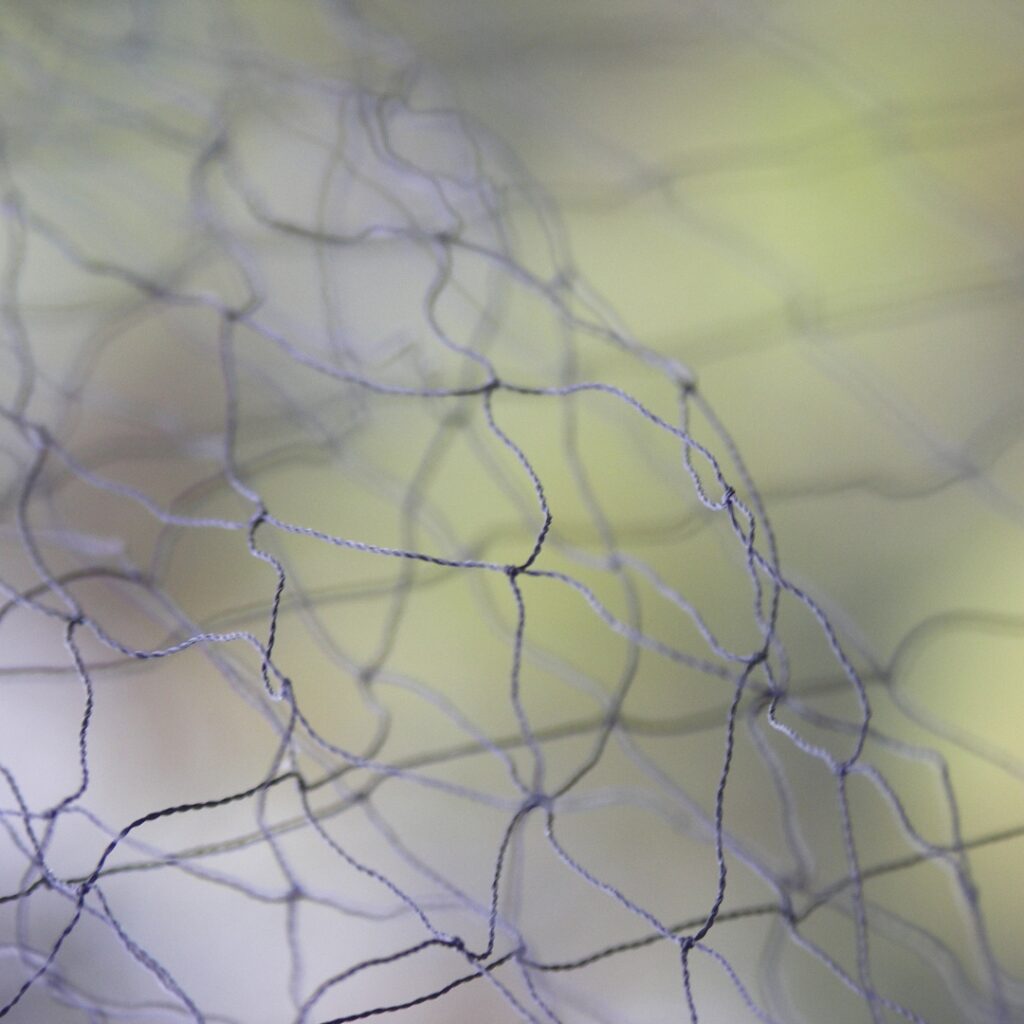

Trained professionals conduct all capture and banding under a federally authorized Bird Banding Permit issued by the U.S. Geological Survey’s Bird Banding Laboratory and the State of Ohio. To capture birds, swaths of pocketed netting (shown below) are strewn between staked poles. The delicate mesh nets are nearly invisible and resemble mist, especially in morning light. Nets are continuously checked for birds, and once a bird has flown into a section of netting, it is promptly removed and taken to a nearby banding station.

There, the team affixes a lightweight aluminum band on the bird’s leg and collects information such as sex, weight, and wing length. They also look at the bird’s body condition, checking for signs of injury and features that help determine age. Once data is recorded, the bird is released. It’s a quick process, yet it yields long-term scientific data shared by bird banding stations throughout the United States and Canada. Banded birds that are recaptured provide valuable information about species’ population and reproductive rates, habitat usage, and migration routes.

Although conducting bird banding is relatively new for CVNP, Gutierrez is excited that the park’s division of resource management is working to establish a long-term migration monitoring program. She cares deeply about bird conservation and has spent over 20 years working with birds. Both her master’s and doctoral work focused on studying migratory birds, but one of her earliest field experiences occurred 18 years ago in CVNP as an international intern.

Gutierrez was part of a National Park Service exchange program called the Park Flight Migratory Bird Program. She explains, “Its goal was to bring students and biologists from Latin America to work in national parks in the United States. As an undergrad, I was studying birds in my home country of Nicaragua, and one of the reasons I came to Cuyahoga Valley National Park is because we share many migratory species.”

For Gutierrez, understanding that we share bird species with other regions in the world is critical for bird conservation. Whether making a relatively quick layover during migration or staying for longer periods of time for breeding or wintering, migratory birds depend on multiple locations and habitats during their life cycle. Each of those places is important for the survival of migratory species. “We cannot conserve Wood Thrushes, for example, if we’re not protecting the places where the Wood Thrush makes babies, where it breeds,” she explains.

When we look beyond the boundaries of our own national park, we can better see how interconnected ecosystems are. Monitoring migratory birds, banding birds, and sharing recapture data has implications for how we understand migratory patterns, habitat use and loss, bird populations, and conservation efforts. “We have to work collaboratively with our partners all over the country and with our partners in Canada and Latin America to make a difference for migratory species,” says Gutierrez. “Our birds are not just our birds—we share them—and we have to understand how we’re connected if we want to protect them.”

Note: The Northern Waterthrush (pictured above) breeds in deep, forested wetlands found in northern North America and spends winters in wetland habitats throughout Mexico, Central and northern South America, and the Caribbean. They are found in Cuyahoga Valley only during migration!